|

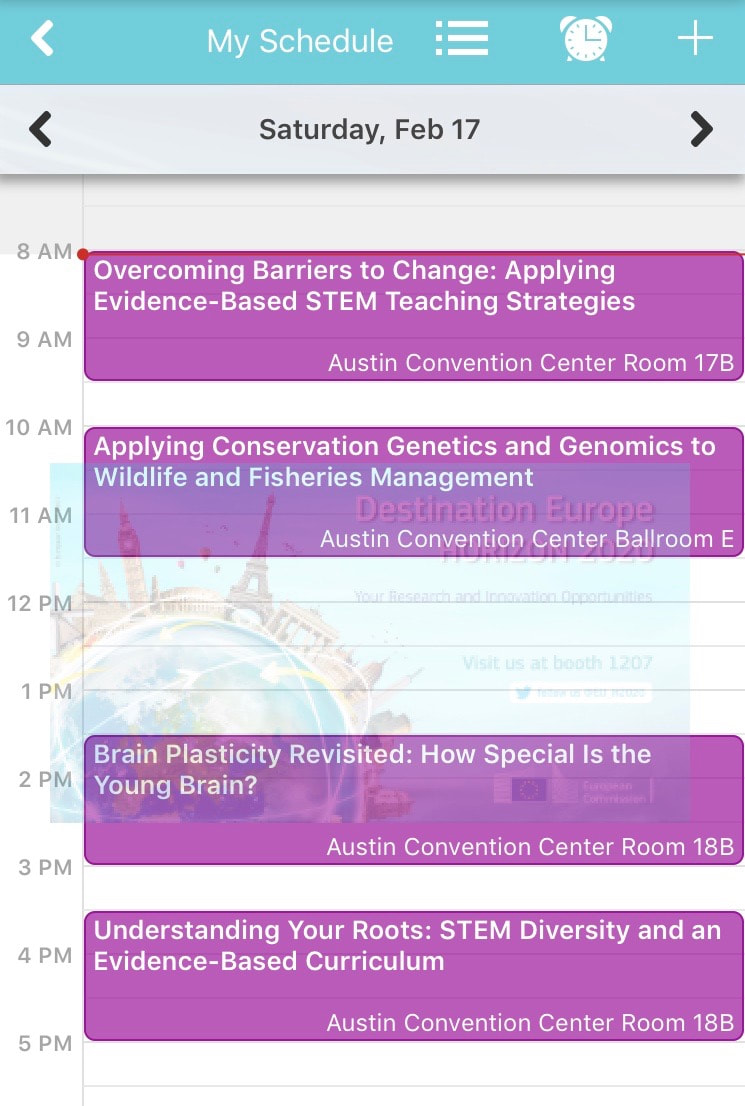

One of the many benefits of being an Einstein Fellow is the opportunity (meaning time and money) to focus on my own learning. In my professional development plan for the year I have included a goal that, “I will strengthen my own scientific content knowledge so that students benefit from an added depth, breadth and interdisciplinary connections.” In alignment with the goal, I attended the annual conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Austin, Texas (14-19 February, 2018). AAAS is the world’s largest multidisciplinary scientific society, and publisher of the renowned journal “Science.” I had never been to Texas and was excited to explore a new place. The timing of conference aligned with a break in Curtis’s work schedule, so we had the added benefit of being able to spend some time together as a family. While I “conferenced” during the day, Curtis and Carrick were able to explore the region around Austin, including going to the Longhorn Cavern State Park (for some cave exploration) and to visit friends and Ferrari’s at the Circuit of the America’s racetrack. Together we were able visit the Waco Mammoth National Monument to learn about the nation’s only recorded discovery of a nursery herd of Columbian mammoths, view fossils of the mammoths and other ice age era animals. The AAAS conference was interesting because the session topics were so varied and interdisciplinary. My schedule was packed full of sessions related to my specific interests in the life sciences, scientific communication and education research. One of the most interesting sessions I attended related to LIFE SCIENCE was called “Modifying the Microbiome for Life Long Health.” This was a composite session, with multiple scientists presenting on the same theme, the human microbiome. On a cellular level, we are only 43% human. An adult human is estimated to be made of 30 trillion human cells and 39 trillion microbial cells! The federally funded Human Microbiome Project is currently working to get a snapshot of the microbes found in 250 healthy people at three time points, by sequencing the microbial DNA found at five sample locations: mouth, skin, vaginal, gut and fecal. While the results are still preliminary, a few preliminary conclusions have been found:

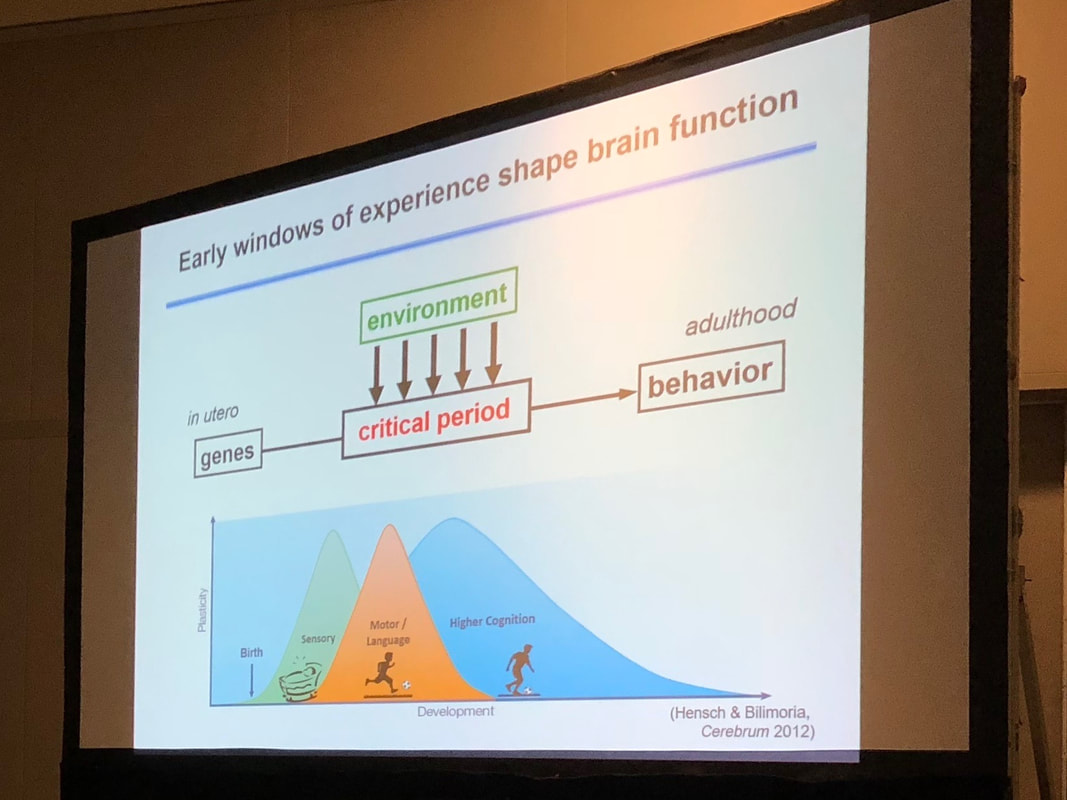

Also on the LIFE SCIENCE thread was a session I attended about brain plasticity and critical periods of learning. It was incredible to hear of the cutting edge research being done to study critical periods of learning and how to either extend these periods or reopen the window for learning. I learned that the closing of critical period is due to formation of a synaptic net, an extracellular network around dendrites which stabilizes neuronal connections. Plasticity can be restored if the synaptic net is removed, but with the risk of destabilizing neurons. Interestingly, a weaker synaptic net is correlated with symptoms of schizophrenia. Another session I attended was about, “Applying Conservation Genetics and Genomics to Wildlife and Fisheries Management.” It was super interesting to learn how genomics is being used to save species in zoos and in the wild by providing information about:

As a teacher, I was also interested in attending sessions related to LEARNING RESEARCH and PEDAGOGY. One of the most interesting sessions was about the shift in undergraduate biology courses towards a more active, engaging methodology of instruction. This is a major shift to the inertia of traditional undergraduate teaching, away from “sit and get” type of lectures to more dynamic and effective methods of instruction that utilize group work, case studies, discussion and student accountability. Interestingly, but honestly not surprisingly, is the measurable resistance by students to the new teaching methods. Students want the “lazy” way of doing school, even though they will admit (and data support) that they learn less via the traditional methods. A crosscutting theme of the conference was the importance and effectiveness of SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION. I attended a session called, “Alternative Facts and Fake News: How to advocate for science when data aren’t enough” with the focus on the need for scientists to communicate more than facts in an era of fake news. I was intrigued that the philosophy of rhetoric, persuasion and communication as originally presented by Aristotle seem to still have relevance today:

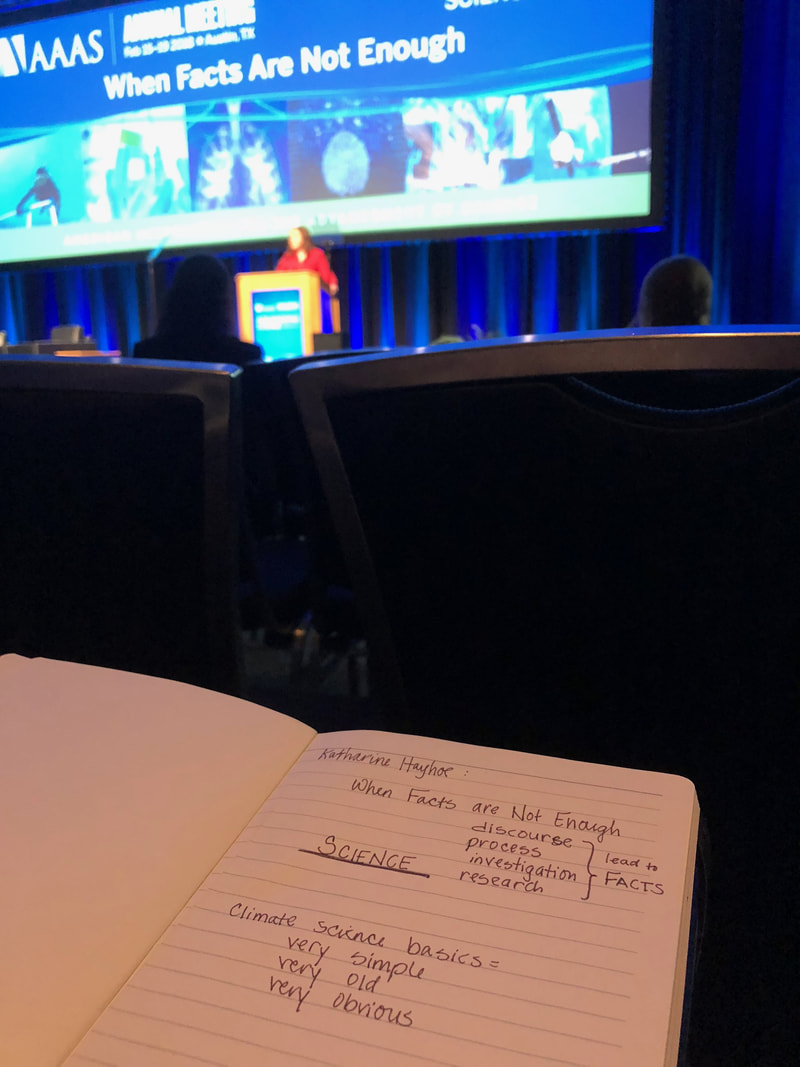

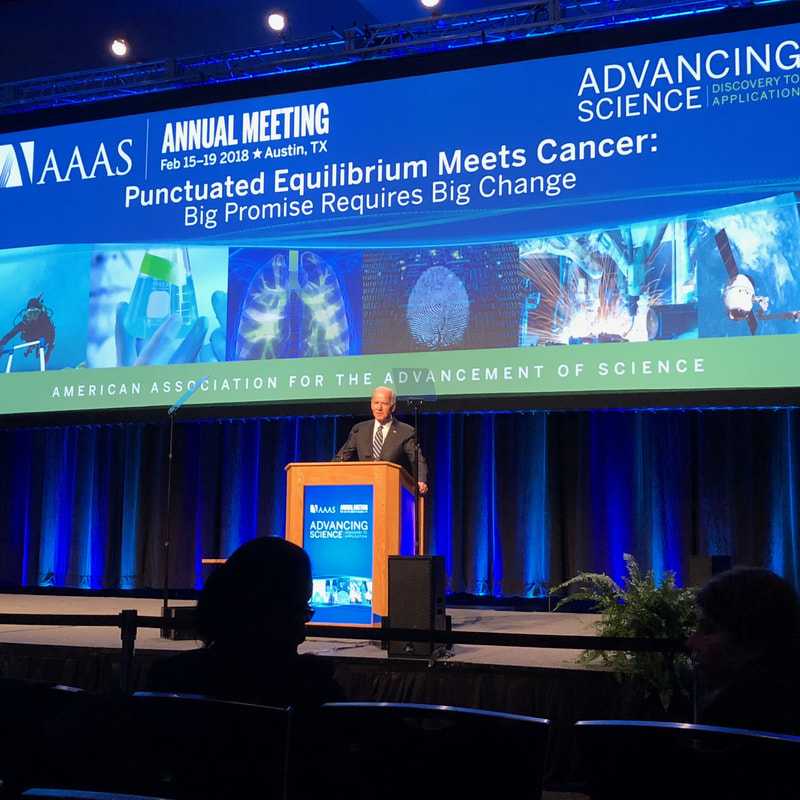

After waiting in line for two hours, I was able to get front row seats for the two conference plenary lectures. The first was by Katharine Hayhoe, a professor of political science and director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University. She is an atmospheric scientist whose research focuses on developing and applying high-resolution climate projections to understand what climate change means for people and the natural environment. In addition, Katharine was the lead author for the Second and Third U.S. National Climate Assessments, with over 120 peer-reviewed publications that evaluate global climate model performance, develop and compare downscaling approaches, and quantify the impacts of climate change on cities, states, ecosystems, and sectors over the coming century. Ms. Hayhoe’s talk, called “When Facts are Not Enough,” provided an overview of the very simple, very old and very obvious climate science basics. Her lecture focused on the reasoning why some people who have no ideological problems with the idea of gravity, cells, or photosynthesis appear to have an ideological disregard for the equally supported science of climate change. Her thesis was that climate deniers actually most have a problem with the perceived solutions to mitigating climate change, not wanting the government to tell them what to do. Fear of solutions > Fear of impact Ms. Hayhoe’s explained that the primary predictors of climate change denialism are age and political conservationism. However, she went on to argue that it is a false dichotomy that you have to be a democrat to care about the planet. NO. In fact, all major religions have a care for the planet theme. “We care about climate change note because we are democrat or republican, we care because we are HUMAN.” So, what can scientists and science educators do? Ms. Hayhoe pointed out that arguing facts makes people more entrenched, that more information does not change minds. She argued that presenting only fear and doom and gloom will not sustain long term change, rather that we need HOPE to sustain us towards the future. She encouraged conference attendees to share stories, connect with people where you live, share impact AND solutions and most importantly to share their heart and passion to change the world. “It’s the passion that makes other people care about things.” The second plenary lecture of the evening was by former US Vice President Joe Biden. Biden led the White House Cancer Moonshot, which resulted in more than 80 new actions and collaborations from the public and private sectors to speed progress in cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care, and worked with Congress to authorize an additional $1.8 billion for investment in cancer research.

Mr. Biden’s presentation was called “Punctuated Equilibrium Meets Cancer: Big Promise Requires Big Change.” Punctuated equilibrium is the idea in biology that (in speciation and evolution) there are long periods of stasis followed by rapid burst of change. He argued that social change follows the same pattern; years of status quo can be interrupted abruptly to create a renewed society. Biden was specifically speaking about cancer research, prevention, treatment and cure, but I couldn’t help but follow the punctuated equilibrium analogy through to other areas of societal and political concern. |

Archives

July 2018

|

I give many of my IB Biology resources away, for the benefit of students and teachers around the world.

If you've found the materials helpful, please consider making a contribution of any amount

to this Earthwatch Expedition Fund.

Did I forget something? Know of a mistake? Have a suggestion? Let me know by emailing me here.

Before using any of the files available on this site,

please familiarize yourself with the Creative Commons Attribution License.

It prohibits the use of any material on this site for commercial purposes of any kind.

If you've found the materials helpful, please consider making a contribution of any amount

to this Earthwatch Expedition Fund.

Did I forget something? Know of a mistake? Have a suggestion? Let me know by emailing me here.

Before using any of the files available on this site,

please familiarize yourself with the Creative Commons Attribution License.

It prohibits the use of any material on this site for commercial purposes of any kind.